STUDIO VISIT:

LESLEY SHARPE

This month, we visited Lesley Sharpe at her print studio in South-East London to find out a bit more about her work and the process behind her poster “There are lilacs, hawthorns and laburnums etc.,” the third artist-designed poster for On the Western Window Pane at the Van Gogh House London.

During the visit Lesley showed some of the process behind the making of her poster and explained how for her, the aesthetic and quality of the materials are informed by the surface they sit on. “Even when you think there’s nothing there, when the paper comes into contact with the water, you realise that there is an ultra-thin layer of ink sitting on top of the water, just kissing the surface.”

The different circles that make up Lesley’s poster are, in fact, monoprints, and in this way, snapshots of a particular moment in time. Like photography, “without light, these materials couldn’t harden and be transformed into how we experience them now. I like the idea of bringing an image into being and then having the opportunity to excavate that image. There’s something archaeological about it.” Within the printmaking process, there are moments of reveal that force some sort of comparison between your expectation and reality.

Before producing this poster for the Van Gogh House, Lesley had never used marbling as a technique in her printmaking practice. It was through researching printmaking processes that were being pioneered around the time Van Gogh was living at Hackford Road that the idea of using marbling first came to her.

Looking for inspiration in Eastern philosophy, processes and techniques as a counter to the House’s west-facing window where the poster would be displayed, Lesley began to research the Japanese marbling technique of suminigashi (floating-ink-dyeing). Through trying to achieve this stone-like marbling, Lesley found herself enjoying creating more “pebble-like blobs” suggestive of petals floating in puddles in the Spring.

Singular petals are like reproductions of each other, trying to mirror themselves and this idea comes across in the process of letting singular drops of solvent take on their own form once they come into contact with the surface of the water. Depending on how much ink is used, what the surface tension is and whether there is any ambient movement each circular mark will be different.

The reflective silver paper Lesley chose to print on has a story behind it too. Whilst browsing in a bric-a-brac shop in East London about 10 years ago, her inky hands gave away her identity as a printmaker. The shop owner happened to have been a print technician in the past and kept a basement full of materials and reams of paper. He gifted Lesley sheets of this beautiful silver paper which she has been using ever since.

After coming into contact with the water, residual droplets sit on this reflective paper as if it were sweating or a steamed up bathroom mirror, but Lesley says that “rather than thinking about some sort of metaphorical reference to reflections, I am always thinking more about how best to make a print on this shiny, silver surface.” The references can be contemplated afterwards, for example the standard A2 size is the same as the size of the poster, and these in relation to buildings and bodies; the posters are displayed in the window facing outwards so passers by have one experience of it, but what about the other blank side? We can think of the way that this work is viewed as being a secondary ‘point of contact’, the first being the relationship between paper and ink.

On a printing press the cylinder and the pressure this exerts on the paper and plate is the crucial point of contact.The curve of the silver paper as it is dropped onto the inky water is very similar to this. In some ways, Lesley has found a way to duplicate the motions of a press through her hands. Machines in a production process often try to mimic the hand or body efficiently and in Lesley’s years of printing editions for other artists, she says she had to be machine-like.

“You have to be able to repeat an image many times over and there needs to be very little difference between them otherwise they get rejected. You have to teach your body to be machine-like, but there’s an economy and efficiency of time and motion that comes with this. These motions are engineered into the machine but less so into us. It’s much harder for our bodies to repeat the same action without tiring.”

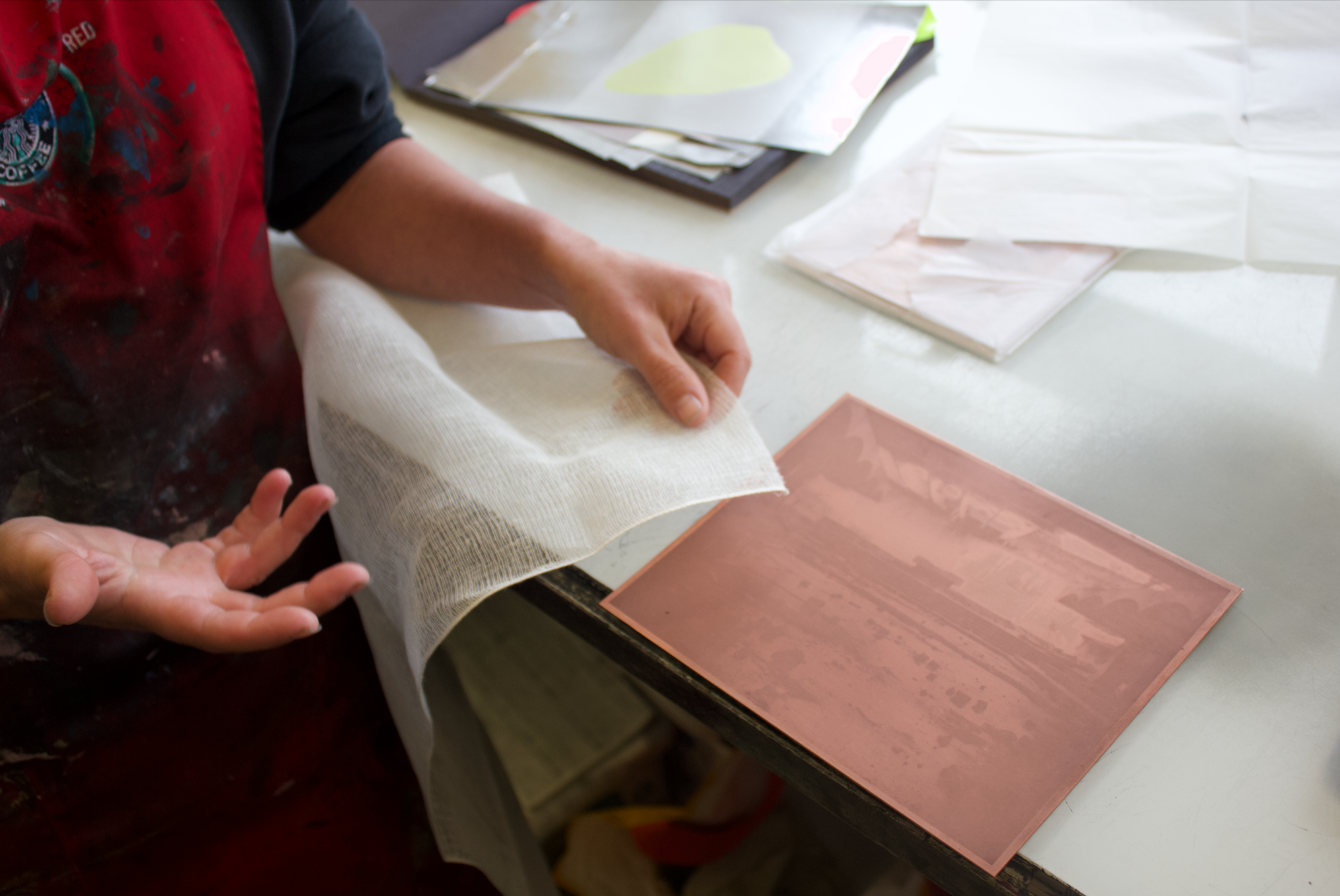

Watching Lesley ink up a copper plate for a different printing process, you realise how physical it is. Even though eventually only a miniscule amount of ink is needed to pull a clear print image, you have to start by completely coating the plate. Then, through a repetitive sweeping motion, you slowly remove it, first with muslin, then tissue paper and then your hand. “It always comes back to the hand, which I really love. The mechanical hand.”

In some ways, the language of print contradicts itself because it’s such a messy procedure but the end result is so clean and considered. The mess has been concealed in some way and perhaps that is through the body. Lesley talks about how her body has changed shape because of the repetitive emphasis on using the right hand side. “I went to a physio a couple of years ago and she said my right shoulder blade has lifted and tilted because I spend almost all my time doing this one motion. It’s quite amazing how your skeleton can start to morph itself without you realising, when you think you’re being really machine-like. It’s shape-shifting.”

Unwrapping a shiny copper plate, Lesley explained to us the process of photogravure which was invented by Henry Fox Talbot in the mid 1800s. “As with all photographic printmaking processes, your image starts with a film positive, so it exists on a piece of acetate which is then exposed onto a piece of gelatin that is adhered onto the copper surface. The image could be a drawing or a mark on anything semi-transparent. In this case it is a photograph of the ruins of St. Peter’s Seminary in Cardross, Scotland; a haunting shell of the modernist building designed by Gillespie, Kidd and Coia in 1958. The main material crucial to the process of photogravure, and that Henry Fox Talbot had a kind of epiphany about, was muslin.”

The grid of the muslin helps to hold tone within the open areas of an image, informing a texture. Nowadays a process called aquatinting does a similar thing, but in the mid-1800s the grid-like structure of the muslin was the most intuitive and logical material to help hold the details within an image.