THE GRIN &

THE GRIMACE

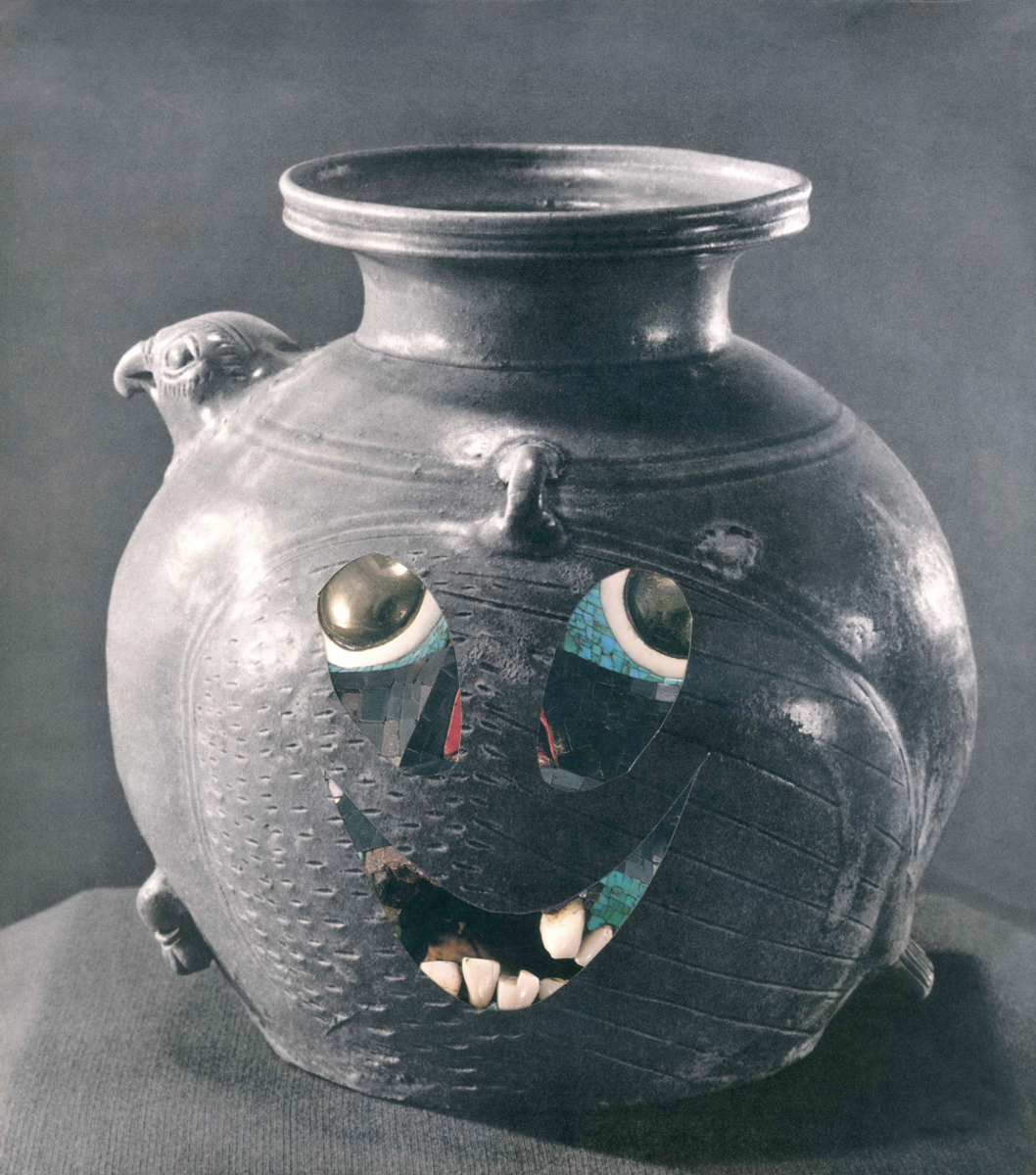

Benjamin Arthur Brown: Maybe the best place to start is with the ‘Vessel Head’ itself – the poster for Van Gogh House. It’s the first to be on display as part of ‘On the Western Window Pane’ and is a wonderful opener, but I was wondering if we could talk about the series it comes from – where and when did ‘Vessel Heads’ start?

Brighid Lowe: It all started when I came across this book of reproductions of Chinese pottery. They were just really high-quality reproductions. There is something special about photographic reproductions from the 1950s and 60s. The standard of actual printing just seems so much better even than now. I was attracted by the resolution and realised as I was looking through, that they seemed to form this parade and I suddenly imagined them as heads.

I had made a previous series [of works] called ‘Citizens of Spam’ where I collected all these different images from colour supplements – which don’t really exist anymore – and I cut out all the pictures of celebrities, actors, politicians and the people in the articles and then cut out this sort of exaggerated smiley face over the top of their features. At that time, I was thinking about Tony Blair and that grin he had, or still very much has, that sort of grin that has an undercurrent. The grin, more a mask of neo-liberalism, the mask dropping from politics at the time, showing the presence behind, the true identity behind.

It was then, in a way, a continuation of that device, but for the ‘Vessel Heads’ it has taken on something a little different.

BB: So, is there an ease to making them, are they premeditated?

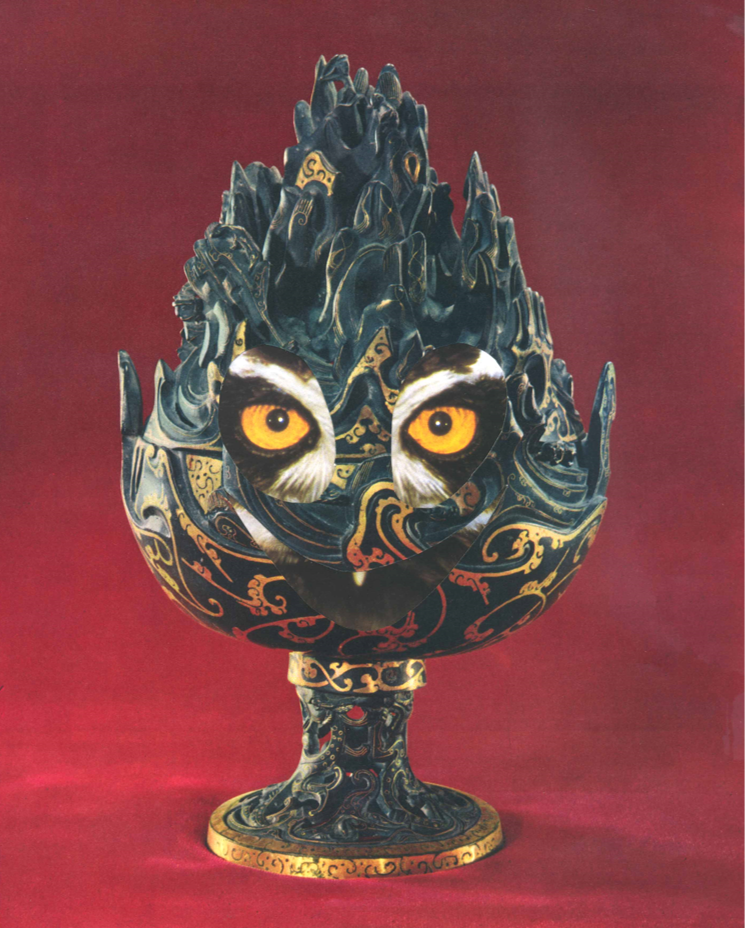

BL: It starts quite formally. You know they become heads with the cuts but in doing so, you free up the space behind, to include another entity, but the emotion has to be right, through that combination. As I started making them, I became compulsive, I had to start collecting, looking for other images of vessels, but they had to be good quality [reproductions] and the same for the faces, or any sort of visage. So, I then was collecting books on animals – birds, cats etc. Anything I can potentially try out. And now I have stacks of these things and it’s a process of just trying different combinations.

BB: As well as the politics in those grins, excuse the pun, there do seem to be layers to these works, beyond the physical layering of two elements.

BL: They are an emotional state. I wanted each one to have a different emotional presence. Some are funny, some melancholy, scary, wistful, or angry or vengeful. For me it’s about a betrayal. They exist as the bringing together, or more like the smashing together of the betrayer and the victim into one entity. You have both the public face but also the internal [face].

BB: That does seem to be the power of these works, maybe of collage as a wider form – there is the surface level quality or image content, but then the combination of two or more of these different worlds or situations. There is also a power in the scale or how they work across different scales, even the difference between seeing them from a distance to seeing them at poster size or larger.

Does this translate across your other works, you work with a wide variety of materials? Maybe even on a formal level – a process of accumulation? Or are there ideas you see through from beginning to end?

BL: Mostly there isn’t any ‘idea’, it comes from visual responses or a sense within a material or image. Definitely things just accumulate. I’ve just started keeping thorns, rose stems, cuttings from the bushes. I haven’t done anything with them yet and I’m not quite sure, but I have a mental image of me gilding them or painting the thorns or even using them as pins to pin up other works. I mean, I haven’t quite had the time, but this is where I start. I’ll try out these instinctive visions and they might work, but they might not, but it leads to thinking of something else.

BB: There’s a restraint and honesty to everything: things allowed to be what they are but placed in situations, much like ourselves, where they are forced to be other, when we can’t be ourselves.

BL: Definitely, I have always collected and then things seems to sublimate themselves. Really, for me, everything is a collage: the process, or acceptance, of allowing things to remain as they are. That’s what I enjoy about the crudeness of the Vessel Heads, you can see what they are. You’re right, from a distance you might be able to read them as a total entity, but then you get closer and it falls apart. I mean it’s almost childish, and maybe deliberately so, but then you are able to see the separate images – in front and behind. But, importantly, you can’t escape that these disparate things are forever chasing one another – perpetually on the edge of being transformed. I’m trying to capture that exact transformative moment and keep it explicit, being held in perpetual transition.

The grin and the grimace in one moment.

BB: I sense a thread back to surrealism and Dada, not just in the use of collage and I wonder if there are particular figures you’ve been drawn to? Or lines of enquiry that you might share?

BL: I suppose, quite honestly, a lot of female artists are from that period in the 20th century. There is that directness [to their work] yet they just weren’t visible. They are [more] visible now, which is great – I think there’s going to be an Eileen Agar retrospective soon – but until recently you would struggle to get a good book on her and there wouldn’t be much work out on show in the world. It has this directness through the materials and combinations. And I have always been a massive fan of Hannah Hoch, which might be a little obvious, but it does have that sort of something…

BB: Meret Oppenheimer?

BL: Yes.

It is a highwire act, though. I don’t think I always manage it. A dangerous or difficult balance. I’m sure some people just see the things: see the books, toys, found objects. It’s not actually straightforward. Some pieces just work better than others. I don’t like to hunt too hard. Everything is a bit ‘Old School’ and analogue. I do like things coming to me or appearing. I have hunted out before, but it always felt forced, but equally through that process you do find things. But sometimes it’s good to work to a brief.

BB: Like for Van Gogh House?

BL: I enjoyed the pressure, having to make it work.

BB: I think it does. It’s difficult, those self-portraits (by Van Gogh) are so recognisable and so often pastiched – even Joni Mitchel has painted herself like that – it’s hard to do something different. And this is effective. As you say maybe crude, although that seems unfair, but effective. Suggestive – there’s the devil horns or ears or even curling biceps in the image. There’s humour.

BL: Humour is so important! Not sure others find it funny, but, for example, when I was making the Coleman Projects show I just didn’t care anymore. I cared about the work, but I relished the unpleasantness and ugliness of the objects. I have tried to crush my instinct about ‘pretty’ work. I do enjoy tasteful and beautifully poised work, and I’m sure I used to try and make a little like that, but I really try and smash it about a bit.

BB: You’ve mentioned your preference for analogue and I sense there is something of an appreciation for 20th century design, furniture and architecture in your selection of materials but also in the display and use of space

BL: Definitely, someone like Gio Ponti for example. There’s an element of surprise to some of his choices. It’s playful yet beautiful and considered. His work feels different to lot of other architects or designers at that point, where it could so easily become its own cliché. He is far more surprising. It also bridges the 50s and 60s and even the 70s and bridges this different aesthetic. It’s disobedient and I like that. I don’t like conforming to too many rules and I especially don’t care about what is ‘current’. What should or shouldn’t be made. I love looking and learning about new and current work and don’t disqualify things because they look or feel ‘current’, but I’m instinctively attracted to things I sense are autonomous and maverick, singular. Things that aren’t conforming to conventions of ‘nowness’ or ‘relevance’.

BB: Maybe this is down to access? The internet. Faster, better, wider access to images and information, and in relation to artists and art. The ‘hunt’ might be different. Things are handed over to us easily now, but I suspect that this is different. Have you seen this as an effect on things?

BL: Like everything it’s a double-edged sword. At moments it’s enabling. People can access anything from anywhere, without having these historic barriers of privileged access. Things were far more ‘exclusive’. But also, there is just so much and it’s just [reduced to] information.

BB: Human beings haven’t necessarily got faster in the same way.

BL: I’m completely redundant, and proud to be. I like the encounter. The serendipity of a moment – when you walk past a place and it triggers a memory. Or the old business of browsing. That does happen online, but not in the same way.

BB: Browsing is somehow controlled now? Written for us? Maybe a little too tailored?

BL: It’s disembodied. I just believe in those particular moments or places or trips. Maybe it’s an idiotic idea of mine, that it’s fate or chance. Maybe it’s because I’m interested in being a romantic cynic or cynical romantic. Those deeper connections you have with these objects, I remember when I found particular things and where. They stick.

BB: So many people, over the past year – for obvious reasons – so quickly started saying that they missed experiences, like going and seeing art. Being with art. It’s just a continuation of what you’re saying but even though I can see a whole show in a New York Gallery from the comfort of my bed now, people are pining for the experiential. I would say that’s a good sign: for better or worse, we haven’t been conquered – that’s definitely the wrong word – haven’t been persuaded convincingly otherwise enough to give up reality and actually things.

BL: I hope so. There are benefits and uses to the digital and even changes that have come out of the last year, that are steps in a positive direction, but I think we have to be careful that they, and us, aren’t exploited for the wrong reasons or motives.

At the centre of it, I love materials and I just can’t retain information the same way when it’s mediated by a computer screen. Conversely, when I go and see a film in the cinema, I can usually remember it better than when I’ve watched it at home. You’re processing with more of your senses. There’s the environmental factor and the scale is very specific and all encompassing. I feel you lose specificity in the digital space. Again, it’s useful for an amount of information but it’s not experiential.

BB: It’s interesting that you bring up Film, or Cinema as it seems to link so well into your work – use of space, qualities of the analogue. I was reminded of ‘Black Narcissus’ at your Coleman Project’s Show. The set painting, the level of trickery, the use of scale, the way things are presented to the audience, a certain camera angle. You had this floating shelf and a tower to present objects. Maybe trickery is the wrong word, but I wonder if this is something you’ve picked up on too?

BL: I’m very interested in the ‘Black Narcissus’ reference because I hadn’t thought about that but find it really interesting. There is something in that definitely. The business of wilful deception, of that trompe l’oeil that really does trick the eye. That state of knowing you’ve been tricked and letting yourself be tricked, but you’re able to be in it. Able to believe and disbelieve simultaneously, which goes back to cynical romanticism.

BB: And the faces caught between polar opposites.

BL: Absolutely. Two opposing impulses. The cut in the collage, in principle destructive but in practice generative. And back again, the elaborate ends you might go to trick someone visually. How considered you have to be. The eye/brain connection. Montage. Again, it’s because film is visual, it’s auditory, it’s emotional, it’s intellectual, it’s conceptual and you can’t separate those elements out. You have the ability to build meaning and content over time and it can creep up on you, that’s the real value. I try and use the logic of the sequence. The logic of reading something – that’s happening with the shelf piece, you are reading along it. That’s also why I show the Vessel Heads together. You read them off of each other. The repetition and the difference.

BB: I like this notion of reading the series, makes me think of them as frames in a film. What you were saying made me think about very long held or almost still shots or the films of Chantel Akerman, or specifically ‘Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels’, where things don’t change for such a long time but because of that you notice those subtle differences, even the grain of the film.

BL: Absolutely. It’s the sum of its parts or greater than. Jeanne Dielmman is so long , but through repetition you see the differences however small and then it has that final scene and is suddenly transformed. Your relationship is then suddenly transformed to everything you’ve seen before that moment. You still remember the ‘before’ but you shift in your cognitive and emotional relationship to the material presented, and all though a single decision.

BB: And equally too, that decision wouldn’t be as poignant or shattering or stark without the rest of the film.

BL: Totally. That’s why I get frustrated with certain approaches to making work or videos where it is constructed purely out of parts that are exciting and meaningful and just linked as a sequence of these moments. For me it doesn’t work like that, at least not in cinema. You have to have travelled there. It only works because of where it has come from, the before and after. I tell people forget that and then it just feels like moments are quoted and maybe a little indulgent.

For me, cinema is about communicating with people. It’s its own art form, it’s the 20th century’s art form. It’s designed for a mass audience, it’s designed to be projected. You sit from beginning to end and that’s how you experience it.

BB: You’re obviously very passionate about film but haven’t really worked with the medium much until now. What made you take the steps to make a film, and a film about Lorenza (Mazzetti)?

BL: It wasn’t necessarily intentional. I’m interested in film and research film and then as a teacher (Associate Professor at Slade School of Fine Art) we have to submit our research for assessment in the ‘REF’, and be seen to apply for research grants. I have this moral stance that I won’t use my own personal studio practice in research funding applications – that would be a betrayal for me and of my [studio] work- so it seemed like a good opportunity to formalise this [film] research. I was looking into this point in the Slade’s history where it had this amazing course, in fact the first university film department, that no one knows very much about. It was run by a film director, Thorold Dickinson and pedagogically we can learn a lot from its structure. It was theoretical but because he [Dickinson] was a practitioner – so there was an intertwining of theory and practice – in an inspirational but straightforward way. I have been working with Henry K. Miller – film historian and writer – who knows a huge amount about it [the Slade Film Department], and we initially just saw the importance of interviewing Lorenza [who was a kind of catalyst for the Slade course]. We didn’t know what we would do with the footage but knew we had to get it and just gather this disappearing oral history. She was really extraordinary.

Then I just became determined to make something of this material. It wasn’t easy, it isn’t easy to work with – and other sources and interviews are sparse or not very good quality – and it wasn’t easy to talk to Lorenza – she lived in an eccentric environment, so there wasn’t much controlling it from our side – there were compromises to be made.

So, I have been able to make my first film because it’s about someone else. It’s not my work directly or my ideas, but I have approached it as if it were my work. Restrictions are put in place: I could only use the footage we shot and what I could access elsewhere, which predominantly are her films and some past recordings of talks. And then we just had to construct a structure that would allow her to speak. A sort of documentary, but not.

It’s like my work in that I have had to watch every second of it over and over and over, almost write all of it down and then work from this, work backwards to create a narrative. Her films are her films, but through this they become a way of showing or embodying her uniqueness through their use here [in the film]. I hope there is a lightness of touch. It’s still her but I have done the arranging.

I was just so aware that she had lived through such seminal moments of the 20th Century, so it felt like a homage or lament for that historical trajectory: that period and its values are going, along with the people that lived it.

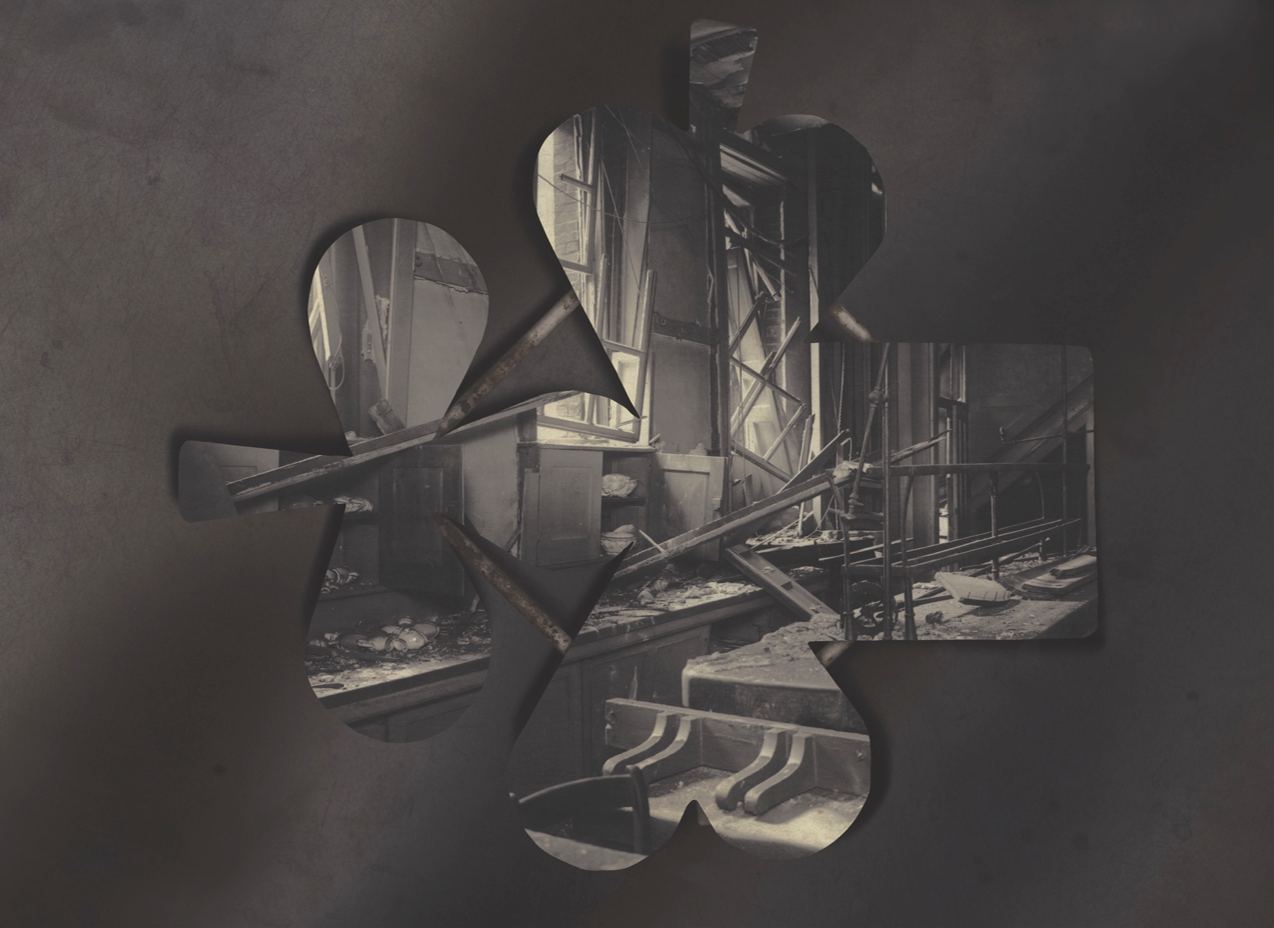

The closest work of my own to this [film] is ‘I Saw Two Englands Break away’, where I write a text through book titles. I couldn’t add any words – yet I still had to make it say what I wanted. I had to transform the material.

BB: And you can’t cheat, it has to be within it already.

BL: Yes, it has to be there within it. We’ve managed to use parts of her films where they are still themselves, but are working for us in another way.

BB: That seems to have been the theme of our conversation: a tension between two points and the creation from this tension. Seems like a nice parallel, to refer back to Ackerman, where you rely on one thing to make the other, but interestingly where that point might be extracted and used and work elsewhere.

BL: In many ways you’re right, that’s how I would usually work – create a tension, but I think I might have done the opposite with this. It’s very much my [standard] methodology, yet [with the film] it’s been more about symmetry or finding resonance: hearing something she said and then trying to find and match it with something else. The difference is that it’s not about me and I’m trying to be truthful to Lorenza. Not impose anything on Lorenza’s work or Lorenza, (although I have had to really impose on the material) but I don’t want to colour how the viewer receives her work or her, which is the contrast to my other work.

Structurally, I think it’s interesting. It has come from two different places. I’ve never worked in this way, but I have had great support, and working with Ginte (Regina) has been a real pleasure. We seem to read things in the same way. Because I’m analogue, I go and have to work out how we put things together and then we do, and you realise it doesn’t quite work but we both know exactly what’s wrong and she can sort it. It’s been reciprocal.

BB: Some harmony.

BL: Harmony.