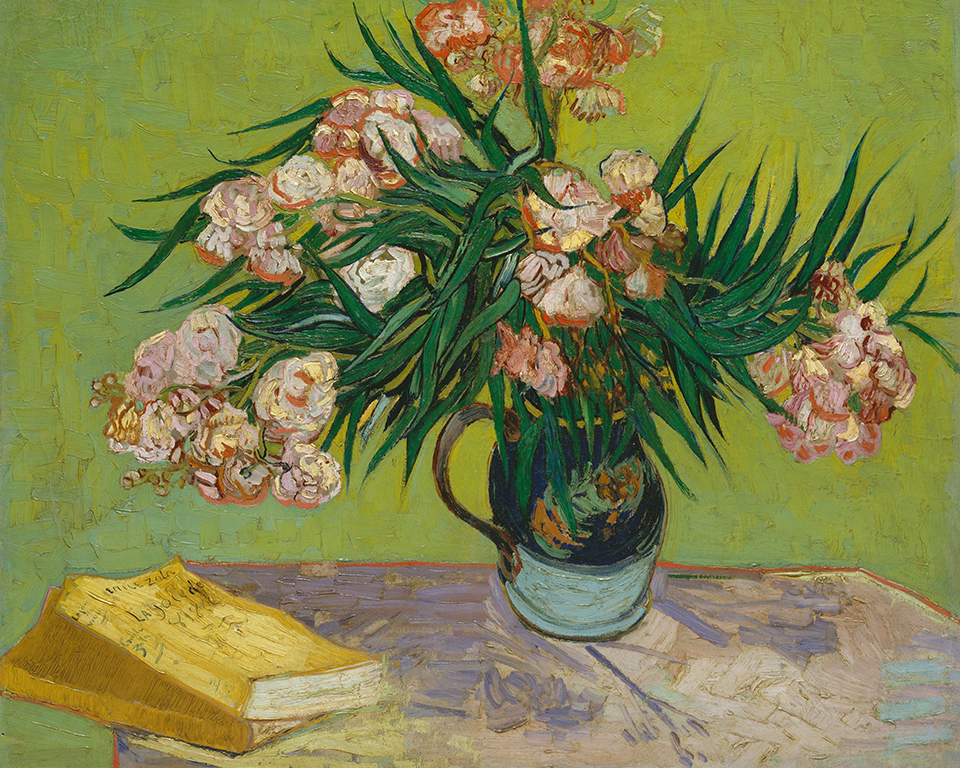

Vincent van Gogh (1853 - 1890), Oleanders, Arles, August 1888, Oil on canvas, 60.3 x 73.7 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

About the Text

During his time in London Van Gogh developed a love for British literature and authors that would shape his life and art in years to come. Vincent wrote extensively to his family and friends, often copying out extracts from his favourite novels, poems and bible passages. Vincent’s letters were uncommonly articulate and poetic for a man who was not a professional writer, a command of language that arguably came from the prose and poetry he read.

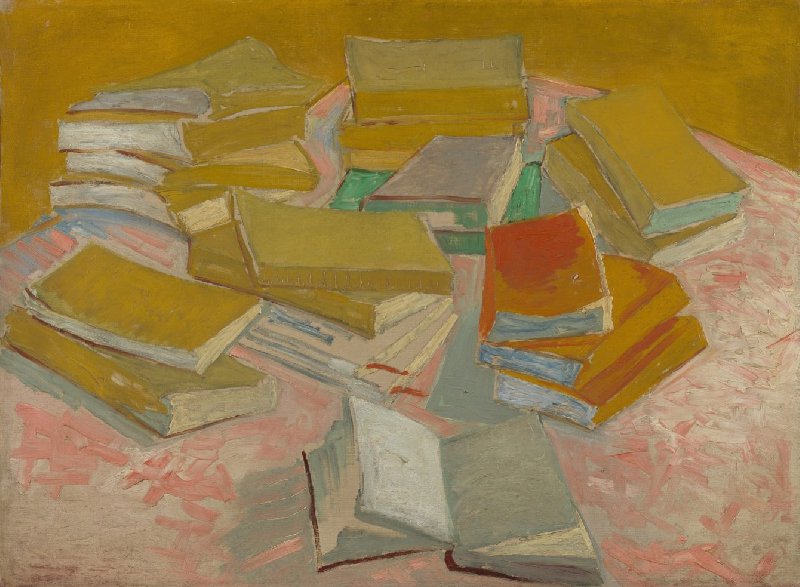

Vincent van Gogh (1853 - 1890), Piles of French Novels, Paris, October-November 1887, oil on canvas, 54.4 cm x 73.6 cm, Credits: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Reading in the 19th Century

During the 19th Century reading became a more accessible pastime with higher literacy rates due to wider access to education. The number of novels available increased greatly during Queen Victoria’s reign in part, due to the cheaper costs of publications and improved distribution due to better transportation. Novels were available in many different forms and through various outlets. Many were available in weekly or monthly instalments with authors leaving readers on a cliffhanger waiting with anticipation for the next issue. Many of Charles Dickens’ novels were first published in this fashion as well as George Eliot’s Middlemarch. This form of production meant that these works were easily accessible with many costing as little as a penny. This format also meant that each instalment was easily shared giving access to more people.

Books for the most part were published in volume form with the most common pattern being three volumes. This meant that the price of new releases was often out of reach for most working class readers. Circulating libraries such as Mudies Circulating Library (founded 1842) were popular among the working class. Books were available to borrow and were sent in boxes across the country to subscribers of the service.Upper class members of society could afford to purchase first editions and would read from their own collections.

6 months after first publication volumes would be available as single volumes instead of volumes of 3. This made volumes cheaper and more available to working class people. Later novels would be available in “railway” or “yellow-back” editions which could be purchased at railway stations for much cheaper. Books that were off copyright were far cheaper which explains why many working class readers were firmilary with Defoe and Fielding. Working class readers were the main consumers of romance novelettes and long running epic series which featured crime and improper adventures that the upper class frowned upon. By the end of the century with the breakdown of publishing three decker volumes, fiction became more popular.

Fiction was widely believed to have an influence on its readers, both good and bad. As George Eliot wrote in an early letter, men and women are ‘imitative beings. We cannot, at least those who ever read to any purpose at all … help being modified by the ideas that pass through our minds’ This idea steamed from the 18th century idea that reading contemporary literature was a waste of time and lacked the cultural seriousness carried by reading classical literature, history or poetry. However fiction had the power to educate the masses teaching of new social ideas. Novels had the ability to guide sympathies toward people whom others would have little in common with. Literature was being used to develop moral strengths such as anti-slavery with Harriet Beechers Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin which was the most widely read novel by the mid 19th century.

Vincent van Gogh (1853 - 1890), L'Arlésienne (portrait of Madame Ginoux), Arles, February 1890, Oil on canvas, 65.3 x 49 cm, Collection Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands

Books in Van Gogh’s paintings

Books appear in fifteen of van Gogh’s paintings and a half a dozen drawings done between 1882-1890. Their inclusion contained special significance for van Gogh and was intended to convey to his sitter and the viewer his own state of mind.

Van Gogh painted a series of six portraits entitled L’Arlésienne (portrait of Madame Ginoux) all depicting Madame Ginoux the proprietor of a café in Arles. Of the four surviving portraits remaining three are nearly identical, featuring Madame Ginoux in a black and white bodice set against a background of pink diagonal strokes. Set on the table are two books, ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ by Harriet Beecher Stowe and Charles Dickens’ ‘Christmas Stories’. The inclusion of these titles was intended to uplift and comfort both Madame Ginoux, who was suffering from a nervous ailment, and the viewer.

Reading List

Van Gogh read widely, embracing all the new teachings and ideas portrayed in novels and literature of the century. Vincent earned a large wage of £90 from his job as an art dealer at Goupil & Cie in Covent Garden. This wage would have enabled Vincent to purchase books and allowed him to read prolifically. We have compiled a reading list so you too can read like Van Gogh and gain insight into his thoughts and values.

Charles Dickens

-

‘A Christmas Carol’, 1843

-

‘Hard Times’, 1854

Above all writers, Van Gogh adored Charles Dickens.The author and the illustrations in his books had a huge impact on van Gogh “my whole life is aimed at making the things from everyday life that Dickens describes and these artists draw”. Van Gogh writes “This week I bought a new 6-penny edition of Christmas carol and Haunted man by Dickens (London Chapman and Hall) with about 7 illustrations by Barnard, for example, a junk shop among others. I find all of Dickens beautiful, but those two tales — I’ve re-read them almost every year since I was a boy, and they always seem new to me… In my view there’s no other writer who’s as much a painter and draughtsman as Dickens. He’s one of those whose characters are resurrections.”

Van Gogh goes as far as to take medical advice from the author, writing to his sister “Every day I take the remedy that the incomparable Dickens prescribes against suicide. It consists of a glass of wine, a piece of bread and cheese and a pipe of tobacco”.

John Keats

-

‘The Eve of Saint Mark’, 1819

-

‘To Autumn’, 1820

In one of his earliest London letters, Van Gogh copies out two Keats poems, ‘To Autumn’ and ‘The Eve of Saint Mark’. He wrote “The last few days I’ve enjoyed reading the poems of John Keats, he’s a poet who isn’t very well known in Holland, I believe. He’s the favourite of the painters here…”

Thomas Carlyle

-

‘On Heroes and Hero Worship and the Heroic in History’, 1841

‘On Heros and Hero worship’ is a collection of six lectures given by Thomas Carlyle: The Hero as Divinity, The Hero as Prophet, The Hero as Poet, The Hero as Priest, The Hero as man of Letters, The Hero as King. Van Gogh mentions Carlyle in several of his letters. Carlyle focuses on how great men play a key focus in history and this history of the world is a biography of great men. This inspires van Gogh to focus on man and the plight of men.

John Bunyan

-

‘The Pilgrim’s Progress’, 1678

‘The Pilgrim’s Progress from this world to that which is to come’ is a Christian allegory and is regarded as one of the most significant works of theological fiction in literature. Van Gogh was a religious man and found inspiration from Bunyan’s work. His father was a Minister and Vincent hoped to follow in his footsteps.

On the 29th October 1876 Van Gogh gave a sermon in Wesleyan Methodist Church in Richmond. The sermon was a nod to Buyans’s work and the classical Christian thought that is central to “The Pilgrims Progress”. Vincent sums up his sermon in a letter to his brother Theo saying “And when everyone of us goes back to daily things and daily duties, let us not forget — that things are not what they seem, that God by the things of daily life teacheth us higher things, that our life is a pilgrim’s progress and that we are strangers in the earth — but that we have a God and Father who preserveth strangers, and that we are all brethren.”

Daniel de Foe

-

‘The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe’, 1719

Daniel Defoe’s pivotal novel ‘The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe’ follows the story of a man who lived for years in isolation on a tropical island. His physical and moral survival is due to his strength of mind and resourceful nature, “even in the most cultured circles and the best surroundings and circumstances, one should retain something of the original nature of a Robinson Crusoe”. Perhaps Van Gogh is reminding himself to remain mentally strong and resourceful,“I sometimes have a certain sense of being abandoned, but on the other hand it concentrates my attention on the things that aren’t changeable, namely the eternal beauty of nature. I often think of the old story of Robinson Crusoe, who didn’t lose heart because of his solitariness but organised things so that he created work for himself and had a very active and very stimulating life through his own searching and toiling”. Perhaps in later life Van Gogh begins to identify with Robinson Crusoe, looking to the fictional character for inspiration and strength as he struggles with his mental health.

William Shakespeare

-

‘The Complete Works of Shakespeare’, 1867

Van Gogh was an avid reader of Shakespeare, mentioning him in several letters to his family, comparing the Bard to a painter, “Shakespeare, his language and his way of doing things are surely the equal of any brush trembling with fever and emotion”Van Gogh goes back to Shakespeare time and time again finding his writing intoxicating. Van Gogh’s love of Shakespeare remained with him while he was voluntarily hospitalised in 1889 in the asylum at St Rémy.

George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans)

-

‘Scenes of Clerical Life Vol. I’, 1857

-

‘Scenes of Clerical Life Vol. II’, 1857

-

‘Felix Holt: The Radical’, 1866

George Eliot was an English novelist, journalist, translator, and poet. Eliot’s true name was Mary Ann Evans who wrote under the pen name of George Eliot. While female authors were published during Evans’s time, she wanted to escape the stereotype and limitations of other female writers and expand beyond light hearted romances. Van Gogh mentions a number of Eliot’s books throughout his letters drawing inspiration from Eliot’s words. Vincent had a deep interest in Eliot’s fiction and her mode of describing the ordinary matters of “provincial life” and elevating them into something luminous. In a letter to his brother Theo Vincent describes the landscapes of Eliot’s works “That landscape – in which a dull yellow sandy road leads over the hill to the village, with mud or whitewashed huts with green, moss-covered roofs and here and there a blackthorn, on either side brown heather and bunt and a grey sky, with a narrow white strip above the horizon”. Eliot’s works inspired Van Gogh’s art, encouraging him to explore everyday scenes of life elevating them into captivating works.

Harriet Beecher Stowe

-

‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’, 1852

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’, had a great impact upon Van Gogh, the book becoming a form of gospel for Vincent, “Take Michelet and Beecher Stowe, they don’t say, the gospel is no longer valid, but they help us to understand how applicable it is in this day and age, in this life of ours.”

Van Gogh read the book a number of times reputedly saying of Beecher “I’ve re-read Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom with extreme attention precisely because it’s a woman’s book, written, she says, while making soup for her children”.

The book put American slavery and freedom into a new perspective for Van Gogh, and he describes it as an “astonishingly beautiful book” where “this extremely momentous matter is treated with such wisdom, with a love and a zeal and interest in the genuine welfare of the poor and oppressed, that one can’t help coming back to it again and again and finding more in it each time.”

The ideas that Stowe were advocating in ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ were progress for their time, however one must think critically when considering this work in the context of today’s society.